Great Horned Owl

(Bubo virginianus)

Introduction

Owls are considered intelligent, mysterious, intriguing and even spooky.

From the time we begin to read we are presented with “wise” owl characters:

the owl in “The Owl and the Pussycat", Wol in “Winnie the Pooh”,

Archimedes in “The Sword and the Stone“ and Hedwig, Harry Potter’s

best friend in “The Philosopher’s Stone” to mention a few.

The idea that owls are intelligent is very pervasive…..for example - what do we call a group of owls?… a flock? a flight? a gaggle?…no, most commonly owls are referred to as a “wisdom” of owls or a ‘"parliament" of owls.

Their exceptional eyesight and hearing support the concept that owls are “wise”. Formidable hunters even in low light, their sensory acuities suggest that owls see and hear what others don’t and thus are symbols of insight and perception.

This web page focuses on the most common owl of BC and the Sunshine Coast, the Great Horned Owl, (GHO) and is intended to increase our understanding and appreciation of this amazing raptor.

Range

The Great Horned Owl is one of the most common owls in North America, equally at home in deserts, wetlands, forests, grasslands, backyards, and cities. This bird does not find it necessary to make seasonal migrations. Banded owls that were later recovered had moved less than 80 km from where they were born. GHOs are most likely to establish a year round residence with a hunting range of 8 to 10 square kilometres. Quoting from Hinterland Who’s Who, “Such adaptation by a species is truly remarkable and has few parallels in ornithology.” In other words, it is hard to find a bird that can adapt better than the GHO.

Characteristics

Widely spaced on the owl’s head are the feathery tufts that have given it the name “Great Horned”. It must be noted that these tufts of feathers are called plumicorns, and are neither horns nor ears

Size:

According to birdwatchinghq.com these are the size statistics for the Great Horned Owl.

Length: 17-25 inches (43 – 64 cm)

Weight: 2.5 to 4 pounds (1134 – 1814 grams)

Wingspan: 3 – 5 feet (91-153 cm)

Differences between the male and female:

How do you distinguish between the male and the female? As with almost all raptors, the female is larger and heavier than the male. When they hoot, her hoot is pitched slightly higher than the male’s creating that wonderful duet that you might hear some evening.

Click here for a sample "hoot":

A comprehensive site for listening to the hoots, chitter, squawks, hisses and bill clacking is available by clicking HERE:

Colouration:

The GHO has a facial disk that varies in colour from a light orange-buff to brownish-gray and dark brown. Distinctive to this species are the very large yellow eyes and the bright white patch at the throat that expands during vocalization. The plumage is heavily barred with black on the buff or white underparts, while the upper parts are a dark grayish brown mottled with grey, brown and black. We may complain that we don’t see many GHOs but this is frequently because, as they sit quietly in a tree, their colouration camouflages them so successfully.

Feet:

One of the most interesting descriptions of this owl’s feet comes from birdnote.org -“The grip strength in those feet — 200 to 500 pounds per square inch—is equal to that of the much larger Bald Eagle and up to six times stronger than the handshake of a bodybuilder. Talk about a “death grip!

The feet of the GHO have feathers that are touch sensitive. As it swoops in on a prey the GHO knows immediately whether the attack has been successful or whether it has merely twigs and leaves in its grasp. The four toes are adapted so that the outermost toes rotates forward and backwards giving it an advantage when clutching prey (or sitting on a branch). Almost all prey are killed by being crushed by the owl's feet and possibly stabbed by its talons. The GHO is one of a very few birds that has talons longer than some bear claws.

Wings:

Great Horned Owls have unique wing and feather features that enable them to be very stealthy predators; the kind of predator that relies more on surprise than speed. Wing feathers have comb-like serrations on the leading edge and a wispy fringe on the trailing edge. In flight, this allows the air to slip through the feathers and makes the GHO one of the few birds that can flap its wings without producing a “swooshing” sound.

They have large wings relative to their body mass, which let them fly unusually slowly. At night…. gliding noiselessly…. slowly…. with little flapping—you can imagine how the prey doesn’t get any warning and doesn’t know to run before it’s too late. In the following video you can’t help feeling sorry for the mouse.

Eyesight:

There are many extraordinary things to say about this owl’s eyes, but foremost is simply how enormous they are. The GHO’s eyes make up as much as 5 percent of this birds' total body weight. That may not sound like a lot, but in comparison, our eyeballs are about 0.0003 percent of our total weight. Humans would have to have eyes as big as softballs to be of comparable size.

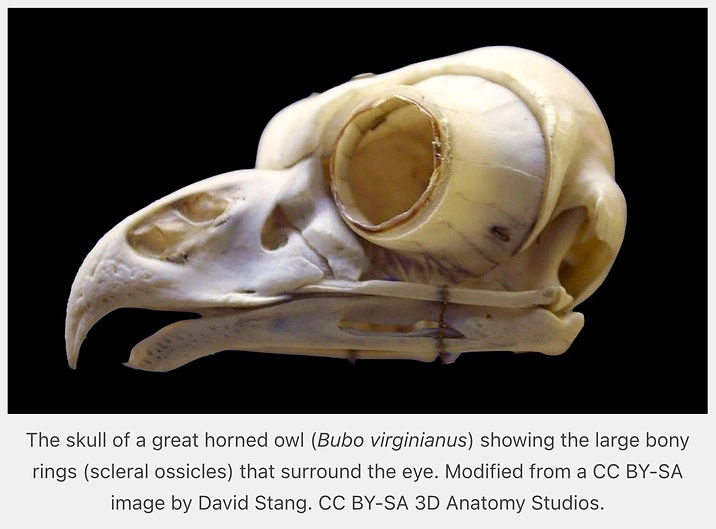

The owl’s eyes are held in place by a bony structure called a sclerotic ring. Due to the size of the eyes, there is no room left for the muscles that would control eye position and movement. This results in the piercing “stare” as the owl is only able to look straight ahead. To have a wider field of vision, the owl must turn its whole head. Fortunately, the vertebrae and arteries in the owl’s neck are adapted to allow the head to swivel 270 degrees.

These enormous eyes have pupils that open wide to take advantage of low light. The GHO’s eyes are actually not round, but cylindrical in shape which creates more distance from the lens to the retina. Compared to round eyes, the GHO’s eyes function more like a telephoto lens allowing clearer sight at a greater distance. They have more rods than cones which means they have poor colour vision and excellent night vision. As well, they have a translucent “third eyelid” that closes horizontally from the inside corner of the GHO’s eye. These nictitating membranes protect their eyes from dust and debris when in flight.

Hearing:

The ears of the Great Horned owl are actually just simple holes in the bird’s head on either side of the face. These “holes” are hidden under the curved lines of the dark feathers that form the facial disc. The GHO can actually raise these short facial disk feathers to amplify sound, similar to you cupping your hands behind your ears. The Great Horned Owl’s hearing is so acute that even at a considerable distance it can discern small prey moving under leaves and snow. What is even more interesting is that their ears are actually offset with the right ear being a little higher than the left. This allows the owl to be able to triangulate sound. It tilts its head until the sound is equal in both ears and at this point, the owl knows it has its prey in its sight line.

Sense of Smell:

Interestingly, a Great Horned Owls’ sense of smell is so weak that they even attack and eat skunks!

Diet and Digestion:

The GHO, in keeping with its reputation for being adaptive, is described as not being “picky” about what it eats. Although it prefers mammals such as rats, mice, voles, rabbits and ground squirrels, it will eat birds up to the size of geese, ducks, hawks and small owls. Snakes, lizards, frogs, insects and even occasionally fish can become part of its very diverse diet.

Owls usually consume smaller prey whole. They have a two-part digestive system. The first part of this digestive system breaks down the soft tissues and then sends the fur, bones and other remains to the gizzard. In the gizzard what can’t be used undergoes a kind of trash compactor action that produces a pellet.

The owl will not be able to eat again until it gets rid of the pellet. Ten to twelve hours after a meal, when the owl is hungry again, its esophagus will spasm and the pellet will be ejected from the gizzard.

Life Cycle

Courtship:

Courtship by Great Horned Owls is brief and rather short on romance – a bit of head bobbing, hopping, occasional beak snapping, and some feather fluffing. All the while they hoot back and forth. At some point, the male brings the female a mouse or some other bit of food and this seems to convince her that he will be an adequate provider.

Reproduction:

GHOs mate in January and early February. Again, in keeping with their habit of being flexible and “not picky”, they very often just move into a used nest and don’t engage in any “renos”. The female will then lay one to five eggs, but typically two. She immediately begins incubating these eggs for approximately 30 to 37 days. The female does all the incubating as she has a featherless area on her abdomen called a “brood patch”. This area has many blood vessels below the skin and is designed to keep the eggs warm. During this time the male is busy bringing her food.

The following has been summarized from the Cornell Lab Bird Cams FAQ site and provides a look at the development of the young.

Day 1: The chicks are unable to raise their heads, lie limp and are totally dependent on their parents to feed them. The young have pink legs and skin and are covered with white down. Their eyes are closed.

Day 3: The young will start to raise their heads.

Day 6: The young will start snapping their bills.

Day 7: The young are able to cast their first pellets.

Day 9: Eyes may start to open.

Day 14: The owlets are able to locate the parents by sound. They will respond with food calls or whimpers when the adults hoot.

Day 15: The young will start to exhibit hostile behavior when intruders approach the nest. They may hiss, sway from side to side, snap their bills, and raise their wings.

Day 20-27: The owlets are able to feed themselves, with food brought to the nest, although the female parent may continue to feed them.

Day 40: The young are able to climb well, at which time they may leave the nest and clamber out along a tree branch. This stage is known as branching.

Day 45-49: The young are fully feathered and capable of of three to four short flights of diminishing distance as they tire easily.

After leaving the nest, the fledglings stay together for awhile and the adults may still bring them occasional food items, depositing them, and leaving the young to dismember and swallow the prey on their own.

Although estimates vary, the GHO is thought to have a life span of 10 to 20 years. Occasionally earlier, but generally at two years of age the female begins producing a clutch of eggs once a year.

Population Numbers

Although great horned owls are classified as of “least concern”, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the global population is estimated at 6 million, with 14 per cent living in Canada. The total population decreased by about 33 per cent between 1966 and 2015.

Canadian populations have had even greater declines, with a loss of 72 per cent.

This seems like a significant decline and many of us are noticing that fewer birds, in general, are showing up on our deck railings and sharing their songs with us from nearby trees. According to the article “Major Threats to Birds in Canada” (birdscanada.org) the main reasons for bird mortality are listed as:

-

Habitat loss…The primary drivers are land use changes, such as agricultural activity, urban development, natural resource extraction, and infrastructure development.

-

Pesticides and contaminants….Man-made toxic chemicals degrade bird habitats, and reduce the food available to birds.

-

Invasive species and cats…”Predation by domestic and feral cats causes the single largest number of bird deaths (mainly to common and widespread species) of any of these five major threats.”

-

Collisions….The largest cause of individual bird deaths in this category is believed to be collisions with windows in buildings.

-

The Climate Crisis….Changing temperatures and rainfall patterns drive changes in the habitats to which birds are adapted.

What Can Be Done to Help

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology informs us that - "In 2019, scientists documented North America’s staggering loss of nearly 3 billion breeding birds since 1970. Helping birds can be as simple as making changes to everyday habits. Here’s our quick list of 7 Simple Actions you can take to help birds:"

-

Make Windows Safer, Day and Night. The challenge: In Canada between 16 and 42 million birds are estimated to die each year after hitting windows.

-

Keep Cats Indoors. The challenge: This is the No. 1 human-caused reason for the loss of birds, aside from habitat loss.

-

Reduce Lawn, Plant Natives. The challenge: Birds have fewer places to safely rest during migration and to raise their young. Audubon's Native Plant Database can help you find the perfect native plants for your yard.

-

Avoid Pesticides and Herbicides. The challenge: pesticides can be lethal to birds and to the insects that birds consume. In Canada, since 2013, the percentage of households using pesticides has remained stable at 19% and increased slightly to 20% in 2019. In 2017, the federal government re-approved the use of glyphosate until at least 2032. Learn more at American Bird Conservancy.

-

Drink Coffee That is Good for Birds. The challenge: Three-quarters of the world’s coffee farms grow their plants by first destroying forests that birds and other wildlife need for food and shelter. Shade-grown coffee beans preserve forest canopies so birds can still inhabit that environment. Look for the Bird Friendly coffee certification.

-

Protect Our Planet from Plastic. The challenge: It’s estimated that 4,900 million metric tons of plastic have accumulated in landfills and in our environment worldwide, polluting and harming wildlife. Give up single-use plastics, buy in bulk, think refillable, etc.

-

Watch Birds, Share What You See. The challenge: Monitoring Birds is essential to help protect them. Enjoy birds while helping science and conservation: Join a project such as eBird, Project FeederWatch, Christmas Bird Count or Breeding Bird Survey. Your contributions will provide valuable information to show where birds are thriving—and where they need our help.

For an in-depth look at these 7 Simple Actions, and additional supporting information, we encourage you to click on the following link: The Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Project Feeder Watch at: https://feederwatch.org is a joint research and education project of Birds Canada and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology that depends on volunteers like you to help us all learn more about bird populations. Your observations of birds out your window can really help the conservation of Canada's birds.

Interested in inviting a Great Horned Owl to live near you? The following is a site for nest building plans….https://nestwatch.org/learn/all-about-birdhouses/birds/great-horned-owl/

References

Hinterland Who’s Who: https://www.hww.ca/en/wildlife/birds/great-horned-owl.html

Nature Conservancy Canada: https://www.natureconservancy.ca/en/what-we-do/resource-centre/featured-species/birds/great-horned-owl.html

Birds Canada, article "Major Threats to Birds in Canada”: https://www.birdscanada.org/conserve-birds/major-threats-to-birds

Owls of BC's South Coast, Who's Who: http://www.sccp.ca/sites/default/files/resources/documents/SCCP%20OWL%20ID%204pg%20Sept%2027.pdf

The CornellLab of Ornithology, Seven Simple Actions to Help Birds: https://www.birds.cornell.edu/home/seven-simple-actions-to-help-birds/

The CornellLab, All About Birds: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/bird-cams-faq-great-horned-owl-nest/#nest-parent

15 Kinds Of Owls That Live In BRITISH COLUMBIA! (2024) https://birdwatchinghq.com/owls-in-british-columbia/.

Conservancy-“Owl”, Amazing facts about Owl Eyes: https://abcbirds.org/bird/great-horned-owl/

Buffalo Bill Center of the West - My Favorite Facts About Great Horned Owls: https://centerofthewest.org/2013/10/15/my-favorite-facts-about-great-horned-owls/.